To Better Persuade a Human, a Robot Should Use This Trick

SOURCE: SCIENTIFICAMERICAN.COM

DEC 03, 2021

A new study finds that, for robots, overlords are less persuasive than peers.

Karen Hopkin: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science. I’m Karen Hopkin.

Hopkin: Robots can do a lot of things. They can build cars. Stock grocery shelves. Process COVID tests in an automated laboratory. But can a robot change your mind? Well, that depends. Because a new study shows that robots are more persuasive when they’re presented as a peer, as opposed to an authority figure. The findings appear in the journal Science Robotics.

Shane Saunderson: Every year we’re seeing more and more robots, in greater numbers of tasks and environments around our world.

Hopkin: Shane Saunderson, a roboticist at the University of Toronto.

Saunderson: And instead of just 20, 30, 40 years ago—when they were in manufacturing environments building cars or painting things or stuff like that—more and more we’re starting to see them in very social contexts. So in retail environments, in care homes, in schools and things like that. So robots don’t have the luxury of just being functional anymore.

Hopkin: To engage with the humans, they also have to be relatable. For example, imagine a robot helping out in a care facility…delivering a meal or dropping off meds.

Saunderson: You’d often see residents that would refuse to eat their meal or they wouldn’t want to take their medication that day. So you have a care provider have to sit there for 10, 15, 20 minutes having a conversation, reminding that person how important it is.

Hopkin: But could that kind of critical cajoling actually be accomplished by some clever coding?

Saunderson: The reality is if robots are going to take on those types of tasks they do need to know how to be persuasive.

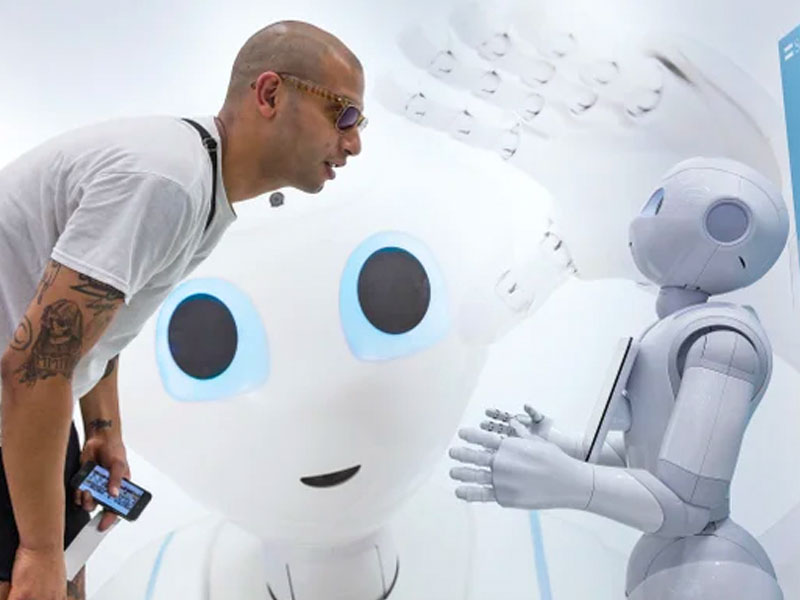

Hopkin: To figure out how to make robots more influential, Saunderson set up a series of tasks. In half the tasks, Saunderson played the role of the experimenter and he would introduce the robot, a programmable off-the shelf model named Pepper, as the participants’ peer.

Saunderson: And so any time someone had to do a task, Pepper would offer suggestions to try and persuade them and help them out.

Hopkin: In one task, a volunteer might be asked to listen to a series of directions…up, down, left, right, right, down, left…and then have to identify their position on a grid based on how well they remembered the list. Here’s Saunderson in the role of experimenter…and participant.

LATEST NEWS

Artificial Intelligence

Eerily realistic: Microsoft’s new AI model makes images talk, sing

APR 20, 2024

WHAT'S TRENDING

Data Science

5 Imaginative Data Science Projects That Can Make Your Portfolio Stand Out

OCT 05, 2022

Amazon Astro offers security monitoring for small businesses

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.THEROBOTREPORT.COM/

NOV 16, 2023

The Future of Grain Storage: Crover’s Innovations supported by The Scotland 5G Centre and CeeD

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.OPP.TODAY/

NOV 01, 2023

These tiny quadrupedal robots are powered by combustion

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.THEROBOTREPORT.COM/

OCT 02, 2023

Battery-free robots use origami to change shape in mid-air

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.SCIENCEDAILY.COM/

SEP 13, 2023

UK robotic dog proves efficiency for UK network maintenance

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.SMART-ENERGY.COM/

AUG 28, 2023

Robotic exoskeletons and neurorehabilitation for acquired brain injury: Determining the potential for recovery of overground walking

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.SCIENCEDAILY.COM/

AUG 22, 2023