Mahindra Lifespaces unveils India’s first home buying experience on the Metaverse

SOURCE: HTTPS://INDIATECHNOLOGYNEWS.IN/

OCT 31, 2023

The metaverse is not designed for women

SOURCE: METRO.CO.UK

APR 02, 2022

n December 2021, Facebook’s parent company, Meta, launched Horizon Worlds, a free virtual reality (VR) space where you could play games and socialise with people’s virtual avatars.

It was the dawn of the ‘metaverse’. Just days after its launch, Nina Jane Patel, a psychotherapist and researcher reported being sexually assaulted there.

‘Within 60 seconds of joining — I was verbally and sexually harassed — 3 – 4 male avatars, with male voices, essentially, virtually gang raped my avatar and took photos — as I tried to get away they yelled — ‘don’t pretend you didn’t love it’ and ‘go rub yourself off to the photo’, she said.

Patel’s experience called attention to a bigger question: Did her experience count as assault? Many did not think so.

The comments on her post describing her ordeal were familiar terms commonly used to dismiss victims of sexual assault: ‘don’t choose a female avatar, it’s a simple fix’, ‘don’t be stupid, it wasn’t real’, ‘a pathetic cry for attention’, ‘avatars don’t have lower bodies to assault’, ’you’ve obviously never played fortnite’.

When Patel’s story was picked up by news outlets, she said the hate escalated and she began receiving death threats and abusive comments on social media and email.

‘Within 60 seconds of joining — I was verbally and sexually harassed,’ (Picture: Nina Jane Patel)

Virtual Reality has three aspects: immersion, where the user feels like they are in another environment, active psychological presence in the virtual environment and embodiment, where users feel like their virtual body (avatar) is their actual physical body.

The intent behind virtual spaces is to make them seem as real as technology permits. The sense of immersion is achieved using patterns of stimulation, including light photons for the eyes, acoustic input for the ears, and tactile or haptic simulators for touch.

So, in that moment — with the technology achieving its purpose — the virtual world was Patel’s reality.

‘When you put a headset on, your real world is blocked out and all you see and hear is the virtual world,’ said Patel, a doctoral researcher of the metaverse investigating the psychological and physiological implications of immersion in virtual environments.

Patel’s avatar when she was assaulted on Horizon Worlds. (Picture: Nina Jane Patel)

‘In some capacity, my physiological and psychological response was as though it happened in reality,’ said Patel, referring to her experience of virtual assault.

The Metaverse — with its components of VR,AR (augmented reality) and XR (extended reality) — has essentially been designed so the mind and body can’t differentiate virtual experiences from real ones.

Hence, the response to a virtual experience can be quite similar to an actual lived experience.

While other media technologies can create psychological presence or the sense of ‘being there’, the scale at which metaverse technologies do it causes users to temporarily suspend the sense that an experience is mediated by technology and instead feel as if they are having a real experience.

‘When recalling memories made in virtual reality and remembering a “real-world experience”, people’s brains react similarly; their bodies react to events in virtual reality as they would in the actual world, with heart rates speeding up in stressful scenarios,’ said Patel.

A Stanford study even showed that younger children could be unable to distinguish between virtual reality and reality, being able to create ‘false memories’.

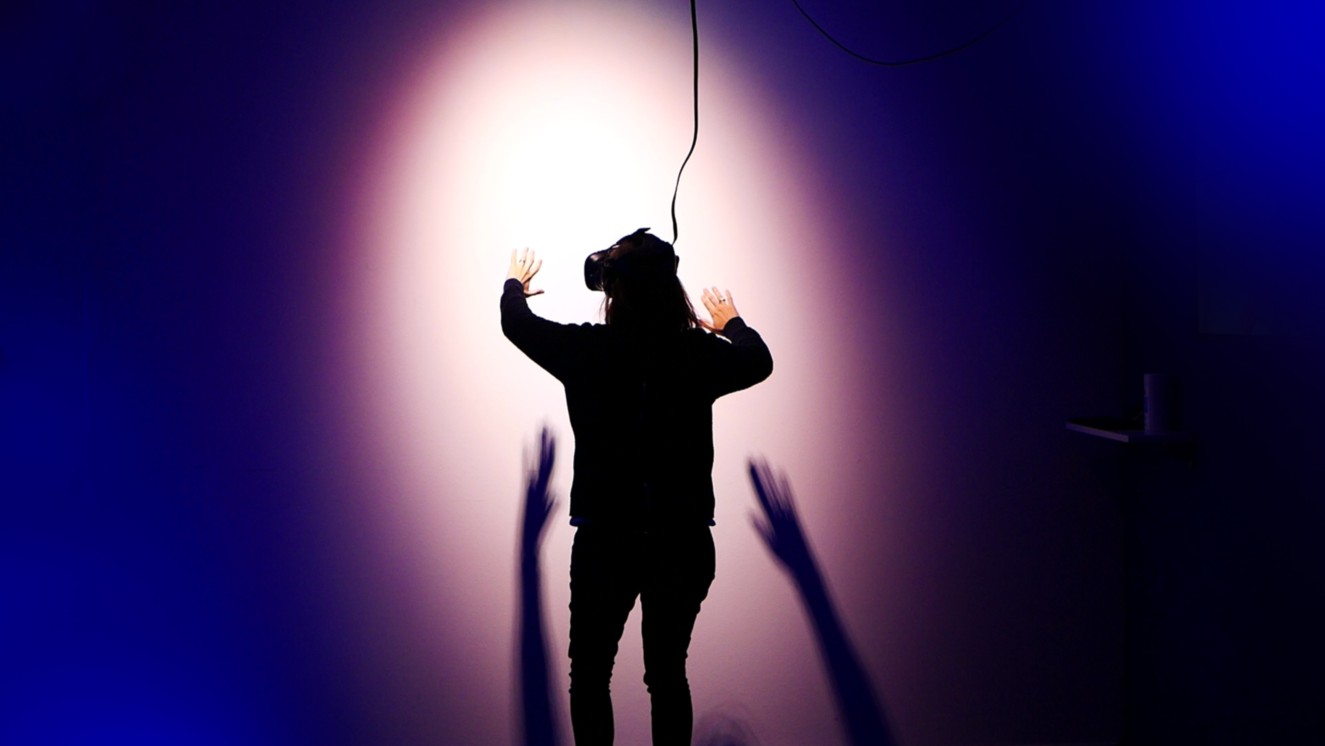

The intent behind virtual spaces is to make them seem as real as technology permits. (Picture: Unsplash)

‘Whether it’s within a game or attending a football match, immersive spaces create heightened experiences, meaning that while pleasant experiences are intensified, unwanted interactions are also made more intrusive and potentially traumatic,’ said Ridderstad, CEO & Co-founder Warpin, a metaverse company.

Some users even report experiencing VR disassociation, the experience of coming out of VR and not feeling connected anymore to your own body, and/or to perceive the physical world around you as not real.

For people who are fairly new to virtual reality, it might even induce anxiety and panic attacks which are likely to dissipate once they get used to it.

So, if something feels so real why hasn’t more thought been given to keep people safe? It could be the question of whose safety is at stake.

Horizon Worlds was released to the public in December 2021 as the first metaverse app (Credits: YouTube / Oculus)

Patel was not the first woman who had reported being sexually assaulted in virtual spaces. In 2016, a woman going by the pseudonym Jordan Belamire recounted her experience of being groped in VR.

Since then, the problem of safety for women in the metaverse seems to have been largely ignored.

In the early days of Virtual Reality (VR), a 2017 study by The Extended Mind found that 49% of female VR users had been subjected to ‘virtual’ harassment.

‘The social cues that you would normally have about someone being creepy or safe weren’t there[…]When people got close to me I felt the same as if someone got close to me in real life,’ said Helen, a 23 year old software developer who participated in the study.

Every big tech company: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google (or FAANG as they’re collectively known) is currently led by men. (Picture: Unsplash)

In her book Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez says that ‘when planners fail to account for gender, public spaces become male spaces by default’ and the metaverse is dangerously close to becoming a male-dominated space.

After all, it’s men that are designing these spaces.

According to 2020 reports, only 20% of tech jobs at Microsoft and 23% of tech jobs at Facebook (Meta), Google and Apple were made up of women. Only 37% of tech startups have at least one woman on the board of directors.

Every big tech company: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google (or FAANG as they’re collectively known) is currently led by men. This gender disparity carries over to the user base as well.

‘Simply by talking to women in gaming you realise how big of a problem harassment and misogyny is in the industry, and how it desperately needs to be addressed,’ said Ridderstad.

‘The metaverse is not going to be an environment that people want to be in unless everyone feels welcome and comfortable there. I think it is safe to say that unless women play their part in building the metaverse and take their place among its architects, it won’t be,’ said Ridderstad.

Avatars in the metaverse (Credits: Meta)

The immersive technology sector has a heavy male gender skew; one that sadly reflects the lack of women in the wider tech industry.

In 2018, quantitative research by King’s College London and the University of Brighton found that only 14% of UK VR companies (registered on Companies House) had any women directors.

‘Since then it doesn’t feel like it’s got any better. This historic lack of women in the sector means that important perspectives get missed out on when products are being funded, designed and built,’ she said.

Limina Immersive, a UK-based research organisation, shows that the gender gap in regular VR users has dramatically increased in the past 12 months.

‘At the start of 2021, men were 35% more likely to be regular VR users than women. The latest data from December 2021 shows that men on average are now nine times more likely than women to be regular VR users,’ said Catherine Allen, the co-founder of Limina Immersive.

‘How VR spaces are shaped and executed right now will directly affect its future and uptake. This does place significant responsibility on the shoulders of early designers,’ she said.

‘There is a pressing need to reconsider the design of the immersive world, and my own experience of sexual assault in the metaverse is just the tip of the iceberg in the digital space,’ said Patel.

There is existing research that discusses the responsibility of constructing new social environments to treat virtual embodiment with the same respect given to physical bodies.

The concept of ‘body sovereignty’ is a VR Design practice that’s being researched in order to construct comprehensive safety features for social VR experiences.

A 2017 study by The Extended Mind found that 49% of female VR users had been subjected to ‘virtual’ harassment. (Picture: Pexels)

‘This research and publishing of academic papers in which metaverse designers (who work for Meta) discuss building the future of inclusive, secure and safe VR communities, happened in 2016. The decision to activate the safety protection measures did not happen until after I shared my story and the headline was “avatar gang raped”,’ said Patel.

So, why didn’t Meta incorporate safety into their design from get go?

‘Most headsets are supposed to be for over-13s, but I’ve encountered children as young as seven talking to men in VR social spaces. I’ve witnessed racial abuse. There are horror stories being published in the news every day,’ she added.

Experts say that the metaverse will be a reflection of the real world and just like the internet we will have dark metaverses and niche metaverses. This also means that predators and all criminal activity will be replicated in the metaverse.

‘As we transition from a 2D internet to 3D, we need to be conscious that the more “real” a digital world seems, the more “real” the experiences within it will feel,’ said Ridderstad.

‘There have long been guidelines on what to do and not to do online, and there are plenty of tools for how to distance and protect yourself. Yet in games and on social media women still get harassed. I have experienced it myself, and I have never spoken to a woman who hasn’t come up against some sort of unacceptable behaviour online,’ said Ridderstad.

Reports and experts agree that the experience of harassment and abuse in VR is not universal. Meaning, it doesn’t apply to straight, white, men.

‘I have observed that this [abuse] is especially the case for women, LGBT people, children and people of colour,’ said Allen.

Virtual spaces without monitored hosting or a purpose are also more likely to breed harassment. Ridderstad warns that we will see problems with avatar bots, just like we do on social media.

‘But because the metaverse is basically the internet in 3D, it will feel much more intrusive,’ she Ridderstad. ‘It’s critical that the software we create now — which will lay the foundations for what will become commonplace — has sufficient ways of reporting harassment and holding users accountable built into it from the very beginning,’

Once Patel’s story made it to mainstream media, Meta responded by adding a security measure to its home-grown virtual world to curtail harassment.

Avatars in the metaverse app Horizon Worlds would now be protected by a ‘personal boundary’ function or ‘safety bubble’ that blocks others from getting too close. The personal bubble will be turned on by default, but users will still be able to make small actions, like high-fives or fist bumps.

But this seems like a mere stopgap; do we keep women in these safety bubbles forever?

Meta’s ‘safety bubble’ blocks other avatars from getting too close and will be turned on by default.

‘Protection features like safety bubbles are helpful, sure, but they should really be the last point of defence – we shouldn’t be in a situation where physical barrier features like this are heavily relied upon,’ said Allen.

Experts say that what we need is effective regulations that are a collaborative effort involving governments, industries, academia and civil society worldwide.

‘The most straightforward solution I can see is platforms like Meta’s Horizon, VRChat and Microsoft Altspace taking more responsibility to foster a positive, healthy culture. Not just through terms and conditions that users tend not to read, but through proactive community building,’ said Allen.

If multiuser open VR environments where strangers can meet each other are here to stay — then it matters what the culture is like in these spaces.

Ultimately, an abuse-free environment starts with the culture and people being aware of the law and what the repercussions might be if they break it.

‘Now is the moment to set the tone and to establish norms,’ said Allen.

The UK is in the process of forming laws to make the internet a safer place and the issue of safety in VR spaces has come up in parliment.

In January, Lord Parkinson clarified that the forthcoming Online Safety Bill was helping to make sure that UK legislation was ‘future-proofed’ to keep pace with new technologies, such as the metaverse.

The Bill might be a start in regulating tech companies – like Meta – creating the metaverse in the UK but this will be impossible through moderation alone with companies rarely investing enough on it.

Mark Zuckerberg reveals Facebook company's new name: Meta

Alternatively, surveilling an online space even for safety comes with privacy issues. This makes proving incidents of harassment and tracking perpetrators tricky unless the player records the incident.

With the Online Safety Bill, the UK government is likely hoping to enable the regulator Ofcom to tackle harm in the metaverse.

In its current state, the Bill only prompts tech companies to ensure user safety by placing controls on user content, rather than any change in their design choices.

We now know that VR can be dangerous both physically and mentally. Just like injuries from bashing into furniture or walls, or an allergic reaction to the headset foam, users are prone to the psychological harm of harassment and abuse in virtual reality.

The question is what do we do about it?

Ridderstad suggests a function before you enter a metaverse space that lays out the acceptable behaviour for forums.

‘One approach could be by rewarding good behaviour, or taking away access or other tokens for failing to meet community standards,’ she said.

Harassment against women in the gaming space is often unprovoked, and many get targeted for just saying ‘hi’.

The first step is to validate the experience of trauma in the metaverse and then proceeding to build a metaverse where underrepresented groups feel safe. (Credits: Meta)

‘Going forward we need to make sure that this is not accepted, and that there will be a consequence for bad behaviour,’ said Ridderstad. ‘We need to move away from the anonymity that protects trolls and misogynists online, and to remind users that people in the virtual space are physical people with real feelings,’

Her VR company, Warpin has even built a VR experience where users can literally walk in someone else’s shoes to understand how they feel.

‘They can choose to play either the role of the bully or the victim, and users get to make choices that impact the outcome,’ said Ridderstad.

In spite of her harrowing experience in the metaverse, Patel calls herself an optimist. Her team at Kabuni are currently designing a safe metaverse for children aged 8-16, to explore, learn and grow.

When you participate in a VR experience, you are doing, not just viewing as your critical distance at that moment is reduced. This means we have to treat the metaverse differently to the rest of the internet.

‘Safety in the Metaverse is a new beast,’ said Patel, calling for progressive laws to create new policies and protocols while asking companies to put safety before profit and scalability.

AR and VR are very different to flat screened rectangular media so it’s not as simple as copy pasting the safety rulebook on what has and hasn’t worked on the regular internet.

‘We also have to speak up when tech companies are literally building worlds (ie. metaverse) that cause damage and trauma,’ said Patel.

‘”Metaverse harassment/bullying/violence/aggression doesn’t exist, just take off your headset!” I hear this all the time but it just isn’t true for those who experience it. This trauma follows us, it lives in our minds and bodies (because the technology has been designed to be as real as possible),’ said Patel.

We might want to be careful not to dismiss or downplay the dystopian potential of the metaverse in order to preserve its utopian reputation as it becomes more mainstream.

‘We can’t innovate or solve problems like toxicity and harassment if we debate their legitimacy at the outset,’ she added.

‘I really feel we need to take digital space seriously, with the same level of responsibility as the physical world,’ said Allen.

‘I find this frustrating, as futuristic assumptions can result in trivialisation and even sometimes a refusal to engage,’

For a lot of us terms such as ‘the metaverse’ and ‘virtual reality’ still feel like they’re part of science fiction but we’re fast approaching a reality where that’s false.

When you participate in a VR experience, you are doing, not just viewing. (Picture: Unsplash)

Catherine believes the core principles that have helped civilisation thrive in the physical world like democracy, human rights, a fair justice system and mental privacy must carry over into the metaverse.

Stories like Patel’s could help refine our understanding of the myriad challenges that metaverse architects are yet to solve.

The first step is to validate the experience of trauma in the metaverse and then proceeding to build a virtual world where where underrepresented groups feel safe.

Maybe then we can start to see the metaverse as a place for women.

Do you feel threatened when using virtual reality or other online technologies? Get in touch at anugraha.sundaravelu@metro.co.uk.

LATEST NEWS

Artificial Intelligence

Eerily realistic: Microsoft’s new AI model makes images talk, sing

APR 20, 2024

WHAT'S TRENDING

Data Science

5 Imaginative Data Science Projects That Can Make Your Portfolio Stand Out

OCT 05, 2022

SOURCE: HTTPS://INDIATECHNOLOGYNEWS.IN/

OCT 31, 2023

SOURCE: HTTPS://FINANCE.YAHOO.COM/

SEP 28, 2023

SOURCE: HTTPS://MEDIABRIEF.COM/

SEP 22, 2023

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.BUSINESS-STANDARD.COM/INDIA-NEWS/METAVERSE-WEB3-MARKET-TO-GROW-40-ANNUALLY-TO-REACH-200-BN-BY-2035-123060200394_1.HTML

JUN 28, 2023

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.WIRED.COM/STORY/WHAT-IS-THE-METAVERSE/

JUN 20, 2023