Pittsburgh isn’t an early adopter of AI but is among ‘fortunate few’ to get involved, Brookings report finds

SOURCE: POST-GAZETTE.COM

SEP 08, 2021

Pittsburgh isn’t an “early adopter” of artificial intelligence research and commercialization but it is a hub for federal investment and conference papers related to the technology, a new report from the Metropolitan Policy Program found Wednesday.

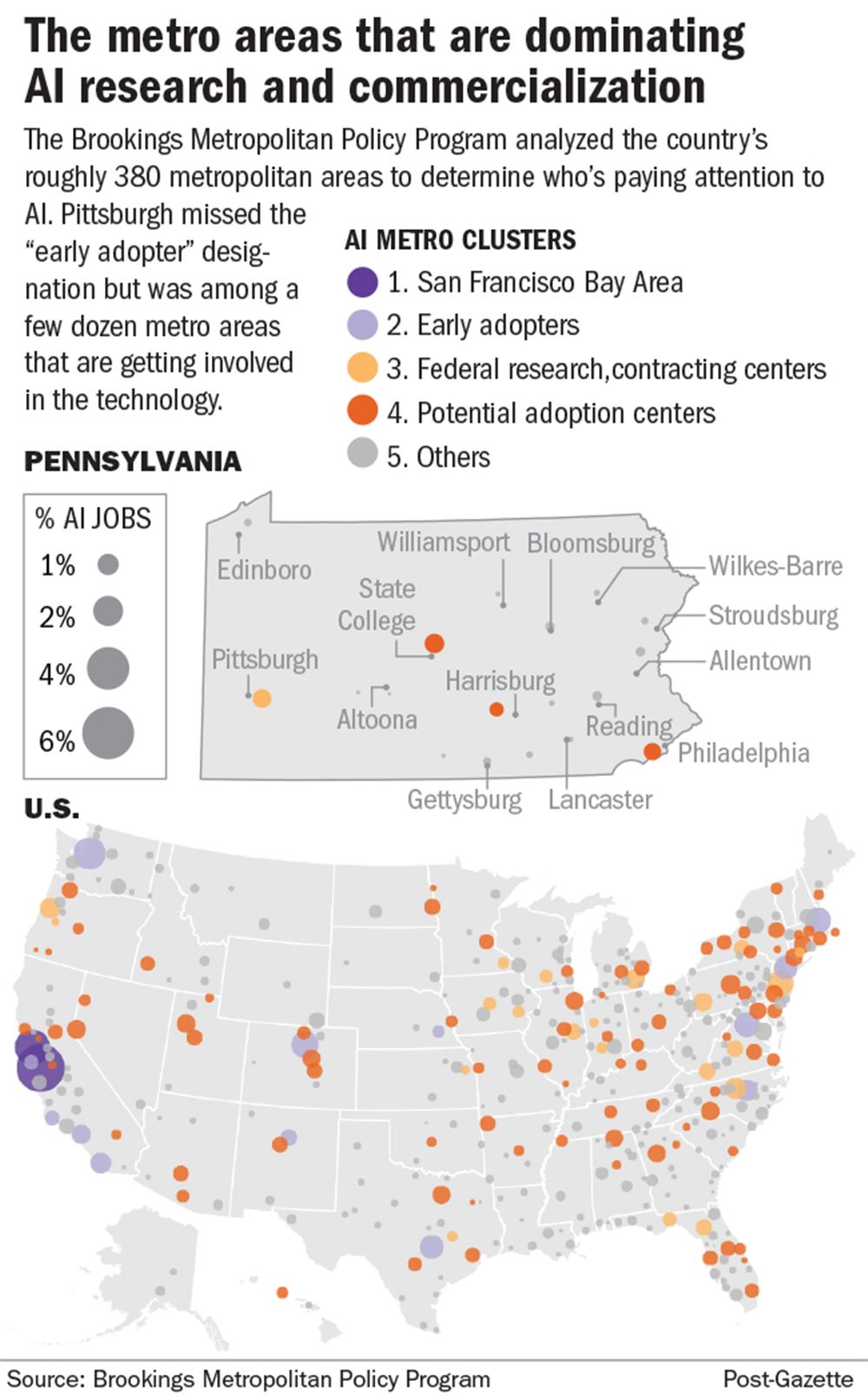

The program, a part of the Brookings Institute based in Washington, D.C., analyzed the country’s roughly 380 metropolitan areas to determine who was paying attention to AI.

“AI is not a realistic economic development priority for perhaps most metropolitan areas,” said Mark Muro, a senior fellow and policy director at the Metropolitan Policy Program. “To that extent, Pittsburgh is among the fortunate few.

“I think the question is can Pittsburgh [and] how does Pittsburgh insert itself into that early adopter tier?”

The report defines artificial intelligence as technology that senses its surroundings and uses those observations to learn, think, predict and make inferences. It covers AI that is used for all sorts of applications, from self-driving cars to voice and facial recognition to anti-fraud measures to chat bots.

AI and its applications could contribute up to $3.7 trillion to North America’s economy by 2030, according to a 2017 estimate from PricewaterhouseCoopers, a professional services network and accounting firm based in London.

The federal government has already invested billions of dollars to support research and development and is considering legislation to expand that funding to more projects and more geographic areas.

So far, most AI activity is concentrated in a cluster of about 15 metropolitan areas, the report found.

The Bay Area in California, including San Francisco and San Jose, accounted for a quarter of the country’s patents, conference papers and companies related to AI. Add on a cluster of 13 metro areas that Brookings defined as “early adopters” and that group makes up two-thirds of AI activity in the country.

Pittsburgh falls just below the early adopter category, which includes tech hubs like Austin, San Diego, Boston, Los Angeles and New York. That group also includes Boulder, Colo.; Santa Fe, N.M.; and Lincoln, Neb.

Pittsburgh ranked as a “research and contracting center,” meaning it’s had success in harnessing federal investment into AI projects, but it doesn’t have as much commercial activity around the technology as the early adopters.

Among the 384 metro areas in the country, roughly 260 did not have any meaningful AI activity, the report found.

The report found another 87 that it considered “potential AI adoption centers,” including State College in Pennsylvania.

Nationally, Pittsburgh ranked 42nd for patents related to artificial intelligence. It ranked 23rd for AI companies, 24th for research and development, 19th for AI job postings and 13th for conference papers.

In explaining Pittsburgh’s lack of commercialization, Mr. Muro invoked a term that has haunted the region before: the brain drain.

The brain drain refers to areas that don’t hold on to their talent. In Pittsburgh’s case, it refers to the people who come to learn at places like Carnegie Mellon University or the University of Pittsburgh but don’t stick around after graduation to use what they’ve learned at local tech firms or to start their own companies.

In a report examining tech jobs in the region between 2013 and 2018, the research arm of real estate firm CBRE also listed Pittsburgh as suffering from brain drain. The 7,800 tech jobs created in those years did not cover the 20,000 people who graduated with a tech degree between 2012 and 2017. So many of them left, the report found.

“The worry is that you aren’t developing enough commercial activity to provide good jobs to the great talent coming out of your universities,” Mr. Muro said. “And the worry is that CMU and Pitt students wind up working in other early adopter metros.”

Mr. Muro is working to avoid a “winner takes most” situation for artificial intelligence, where just a few metro areas reap the benefits of the new technology. That decreases competition, job growth and innovation, he said.

As the report put it, other metro areas could be left off while “the AI rich get richer.”

“AI is critical because it’s likely going to be an important driver of economic productivity in metropolitan areas so to not participate in that economy might mean less productivity growth and a less dynamic economy,” Mr. Muro said.

“That’s not good for Pittsburgh. It’s not good for Pittsburgh workers,” he said. “And it’s ultimately not good for the country if the potential and talent of Pittsburgh is not being leveraged.”

Artificial intelligence is still in the early stages of development. Job postings related to AI accounted for only 0.7% of total positions in 2019 and federally funded AI projects at colleges and universities made up 5% of all research and development expenditures at U.S. colleges in 2018.

But it is growing, Mr. Muro said. That means there’s still time for cities like Pittsburgh to get a toehold in the industry.

“I think this next decade is going to be critical,” he said. “This is moving fast but there is certainly the opportunity to bolster growth in more places.”

Lauren Rosenblatt: lrosenblatt@post-gazette.com, 412-263-1565.

LATEST NEWS

Augmented Reality

Hi-tech smart glasses connecting rural and remote aged care residents to clinicians

NOV 20, 2023

WHAT'S TRENDING

Data Science

5 Imaginative Data Science Projects That Can Make Your Portfolio Stand Out

OCT 05, 2022

AI Is Set To Change Fertility Treatment Forever

SOURCE: HTTPS://CODEBLUE.GALENCENTRE.ORG/

NOV 06, 2023

AI-empowered system may accelerate laparoscopic surgery training

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.NEWS-MEDICAL.NET/

NOV 06, 2023

Here’s Everything You Can Do With Copilot, the Generative AI Assistant on Windows 11

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.WIRED.COM/

NOV 05, 2023

Tongyi Qianwen, An AI Model Developed By Alibaba, Has Been Upgraded, And Industry-specific Models Have Been Released

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.BUSINESSOUTREACH.IN/

OCT 31, 2023

Stability AI Launches Stable Audio — Generate Music Using Artificial Intelligence

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.DIGITALMUSICNEWS.COM/

SEP 13, 2023

Ikigai Labs: $25 Million Raised To Advance Generative AI For Tabular Data

SOURCE: HTTPS://PULSE2.COM/

AUG 27, 2023